Blue Moon is a film about endings disguised as a celebration. Set almost entirely over the course of a single night, Richard Linklater’s latest is deceptively modest in scope, yet quietly devastating in what it reveals about ambition, legacy, and the particular loneliness of realizing your moment has already passed. It’s a talky, intimate character study that trusts performance and language over plot — and in doing so, delivers one of Linklater’s most emotionally precise films in years.

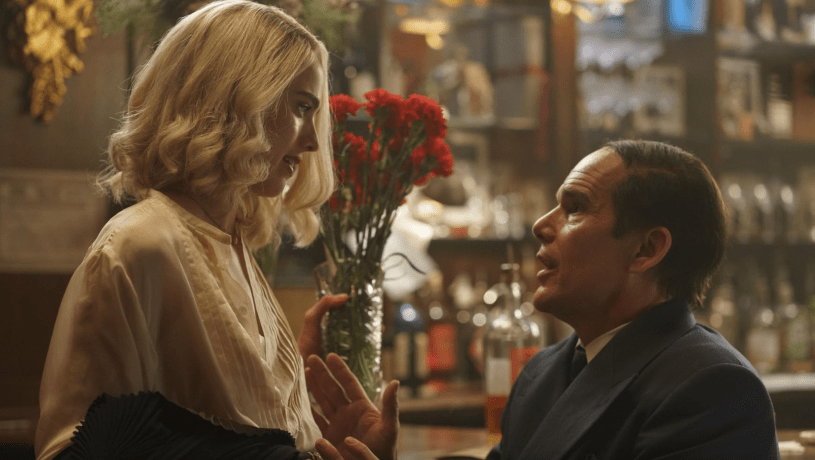

The story unfolds on the opening night of Oklahoma! in 1943, a landmark moment for American musical theatre. While the world celebrates the future, Blue Moon stays behind at the bar with Lorenz Hart, the lyricist who once helped define Broadway but now finds himself eclipsed by both his former collaborator and the shifting tastes of the industry. Ethan Hawke plays Hart with aching specificity, crafting a performance that is sharp, funny, defensive, and deeply sad all at once.

Hawke’s Hart is brilliant and unbearable in equal measure. He talks too much, drinks too much, and intellectualizes his pain until it curdles into bitterness. Yet Hawke never lets the character slip into caricature. Beneath the wit and self-sabotage is a man acutely aware of his own obsolescence — and terrified of what comes next. It’s a performance built on rhythm and timing, every joke landing half a beat too late, every smile carrying a trace of desperation.

Linklater structures the film around conversation rather than incident. Scenes unfold in long takes, often centered on Hart’s interactions with friends, acquaintances, and potential collaborators drifting in and out of the bar. These exchanges are layered with subtext — unspoken resentments, professional jealousy, and the quiet cruelty of being politely dismissed. The dialogue crackles with intelligence, but it’s the pauses and deflections that do the real work.

Visually, Blue Moon is restrained to the point of invisibility, and that’s by design. The camera observes rather than directs attention, allowing performances to shape the emotional arc. The bar becomes a liminal space — a holding pattern where Hart can delay confronting the reality awaiting him outside. There’s an intimacy to the setting that mirrors the film’s thematic concerns: this is a story about being stuck, about watching the future arrive without you.

What makes Blue Moon particularly resonant is its refusal to romanticize creative suffering. The film acknowledges Hart’s talent and influence, but it never excuses his behavior or pretends his bitterness is noble. Linklater understands that genius doesn’t guarantee relevance, and that brilliance can coexist with cruelty, insecurity, and self-destruction. This balance prevents the film from becoming either hagiography or takedown.

That said, Blue Moon is unapologetically niche. Its talk-heavy structure, historical specificity, and lack of conventional narrative propulsion will likely alienate viewers expecting a traditional biopic. The film assumes a certain patience — and a willingness to sit with discomfort — that not all audiences will share. But for those attuned to Linklater’s rhythms, this is precisely where the film finds its power.

As the night stretches on and Hart’s defenses begin to crack, Blue Moon reveals itself as a meditation on timing — in art, in relationships, and in life. There’s no grand confrontation, no climactic revelation. Instead, the film ends with a sense of quiet inevitability, the kind that settles in once the noise fades and you’re left alone with what remains.

In many ways, Blue Moon feels like a companion piece to Linklater’s earlier work — another entry in his ongoing fascination with time and the way it reshapes identity. But here, the focus is sharper, the mood more melancholic. It’s a film about realizing that the spotlight has moved on — and deciding whether to chase it, resent it, or simply let it go.